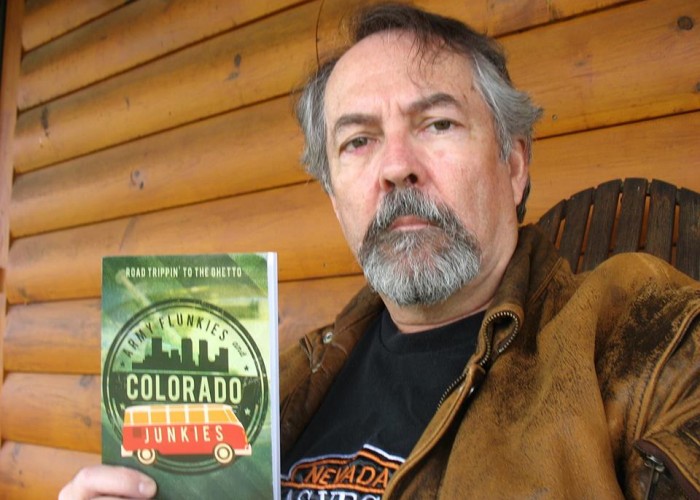

Book Review: “Army Flunkies and Colorado Junkies” by Jed Donavan

Published in the Bennington Banner on Nov. 21, 2013

Original article: http://www.benningtonbanner.com/news/ci_24567497/jed-donavan-rsquo-s-long-strange-trip-local

In his new memoir “Army Flunkies and Colorado Junkies,” local author Jed Donavan offers an honest look into an immense, formative moment in his personal history: Getting clean after years of self-destructive partying and substance abuse. Unfortunately the story is as incomplete as it is interesting — the book skips over the story’s climax, showing his long descent into addiction before snapping straight to a brief, passing snapshot of his present-day success.

The final act of “Army Flunkies” makes it clear that Donavan’s life story is one of extraordinary resolve, strength and redemption. Unfortunately, this book doesn’t seem interested in telling that story. Instead, Donavan seems preoccupied with delivering a provocative “sex, drugs, and rock & roll” story, albeit one with no sex and only occasional music references. So basically, most of the book is just about doing drugs. There’s also some gambling and murder.

Even as episodes of reckless drug use, amateur smuggling and similar mischief dominate the opening chapters, the front matter of the book signals that Jed’s will be a cautionary tale with a positive outcome: The title page presciently labels the story “an addictions memoir,” the acknowledgements reference a 12-step hallmark and the cover promises that the story’s wayward central character will eventually earn a master’s degree. These clues prepare the reader for Jed’s ultimate recovery from the beginning, but Donavan makes us wait too long for the prophecy of salvation to be fulfilled. This excessive test of the reader’s patience effectively drains the potential for final satisfaction at the book’s end.

The main problem with “Army Flunkies and Colorado Junkies” is merely organizational. Instead of focusing his attention on the most impressive and engaging part of the story — Jed’s recovery from addiction and his rise as a counseling psychologist — it gets caught up in the juicy details of his life as an addict, leaning excessively on shocking moments of violence, law-breaking and youthful naiveté. It basically follows the narrative patterns we see in today’s R-rated hollywood comedies: the beginning introduces the characters and environment while making good on marketing promises and pandering to the target audience (The VW bus and slang terms on the cover clearly aren’t meant to attract academics or social conservatives), the middle section establishes and executes the main plot development (in this case being the Denver section, which doesn’t start until page 85) and a short epilogue quickly resolves the whole story.

The book would have been well served by condensing the first section significantly and expanding on Jed’s climactic turn toward rehabilitation. Perhaps the emotional weight of that process makes it too sensitive or difficult to convey, but I’m sure there were moments in Donavan’s path to recovery that were more interesting than the time he tried to smuggle pot on a Greyhound bus.

Donavan’s extended account of addict life is also plagued with problems, especially his one-dimensional, occasionally crass depictions of certain characters. It can be tricky to understand the relationship between real-life figures and their corresponding literary characters in memoirs, but it mainly comes down to the idea of portrayal. While the individuals involved in Donavan’s story are unquestionably real people who may or may not be still alive today, in the “Flunkies and Junkies” universe they only exist as the author portrays them, which can be distorted by memory, outside influences or any number of other things. In this case, Donavan describes himself living in a perpetual state of intoxication during his relationships with certain characters, so distortion is certainly possible. However, being an inescapable part of memoir writing, the idea of distortion itself isn’t the problem here — it’s the way Donavan portrays certain characters that causes problems.

The most glaring example is Donavan’s depictions of Old Jones, an older black man who sometimes acts as Jed’s guide to Denver’s predominantly-black ghettos. Old Jones is introduced as an uneducated former cotton picker from the south, which is probably true and isn’t necessarily objectionable, but Donavan crosses into racial stereotype when he describes Old Jones as speaking in “jive sayings” (page 116), co-opting a slang term with distinct implications. This may be a minor example, but it reflects a pattern of racial insensitivity in the text: On page 153 he refers to a young black man as a “buck” (an unacceptable term, especially because he uses it in a hunting analogy), and during his stay in the Denver ghetto he even likens himself and his (white) friends to the middle part of an Oreo, “being the white filling surrounded by black cookies, waiting to be devoured” (page 135). I shouldn’t have to explain the problems with such charged, reductive language. I don’t think these examples reflect any malicious racial attitudes on the author’s part, he just should have chosen his words more carefully.

Despite some of its functional and characterization flaws, Jed Donavan tells an interesting story and makes some valuable, relevant points in “Army Flunkies and Colorado Junkies.” His writing is honest and raw — bravely sharing his wide range of experiences, even the ugly ones. While his stories about life as a high-functioning drug smuggler and his destitute Denver existence aren’t without their flaws, the book suffers most from Donavan leaving out his rehabilitation experiences, which consequently limits the book’s potential. While there are understandable reasons to avoid the topic, it would help the book resonate on emotional levels that “Junkies and Flunkies” currently doesn’t touch. If he’s saving that part for a sequel, it could be worth the wait.

Donavan’s book is available now locally at Bennington Booksellers an the Northshire Bookstore in Manchester, and on Nov. 26 it will be released on Amazon.com and in major bookstores like Barnes and Noble.

Leave a Reply